Foot Anatomy 101

Comprising 26 bones, 33 joints, and over 100 muscles, tendons, and ligaments, the foot is far more than just a structural base; it is a biomechanical wonder that adapts to various surfaces and activities. This intricate system operates with remarkable precision to provide support, balance, and shock absorption, ensuring smooth and efficient movement. However, its complexity also makes it susceptible to a wide range of conditions when neglected or overworked. By delving into the anatomy of the foot, individuals can gain a deeper understanding of its structure, functionality, and significance in daily life. This knowledge is crucial for maintaining foot health, preventing common conditions, and preserving overall well-being.

Why Understanding Foot Anatomy Matters?

The importance of the foot is often underestimated, even though it is one of the most hardworking parts of the body. On average, an individual takes between 5,000 and 10,000 steps a day, translating to over 100,000 pounds of pressure absorbed by the feet daily (Hicks, 2015). Despite this constant workload, the foot operates silently, facilitating movement without drawing much attention.

However, improper care, ill-fitting footwear, or overuse can disrupt this harmony, leading to discomfort, pain, or even chronic conditions. Issues with the feet can cascade into other parts of the body, affecting the knees, hips, and spine. Understanding the anatomy and mechanics of the foot is the first step toward making informed decisions about footwear, strengthening exercises, and preventive measures, all of which are essential for maintaining healthy and pain-free feet throughout life.

The Framework: Bones of the Foot

The foot's skeletal structure provides the foundation for its intricate mechanics. It is divided into three main regions: the forefoot, midfoot, and hindfoot. Each of these regions serves a specific purpose, and together, they form a cohesive system that enables stability, flexibility, and movement.

1. Forefoot: The Toes and Metatarsals

The forefoot comprises the phalanges (toes) and the metatarsals, which are the long bones leading to the toes. Each toe consists of multiple small bones—three in each smaller toe and two in the big toe—joined by flexible joints that allow a range of motions.

The big toe plays a particularly crucial role in maintaining balance and providing propulsion during walking or running. It can bear up to 40% of body weight during these activities, making it one of the most vital components of the forefoot. When conditions such as bunions arise—a deformity of the joint at the base of the big toe—the delicate balance of the forefoot is disrupted, often leading to pain, instability, and difficulty in walking (Zulkifly et al., 2018).

2. Midfoot: The Arches’ Backbone

The midfoot is made up of the navicular, cuboid, and three cuneiform bones, which form the structural foundation of the foot’s arches. These bones interlock to create the medial, lateral, and transverse arches, which act as natural shock absorbers. They are essential for distributing body weight evenly and adapting to different surfaces.

The medial longitudinal arch, for instance, is the most prominent and supports most of the body’s weight during movement. Any disruption in the midfoot’s structure—such as collapsed arches in flat feet—can lead to improper weight distribution and stress on other parts of the body, such as the knees and lower back.

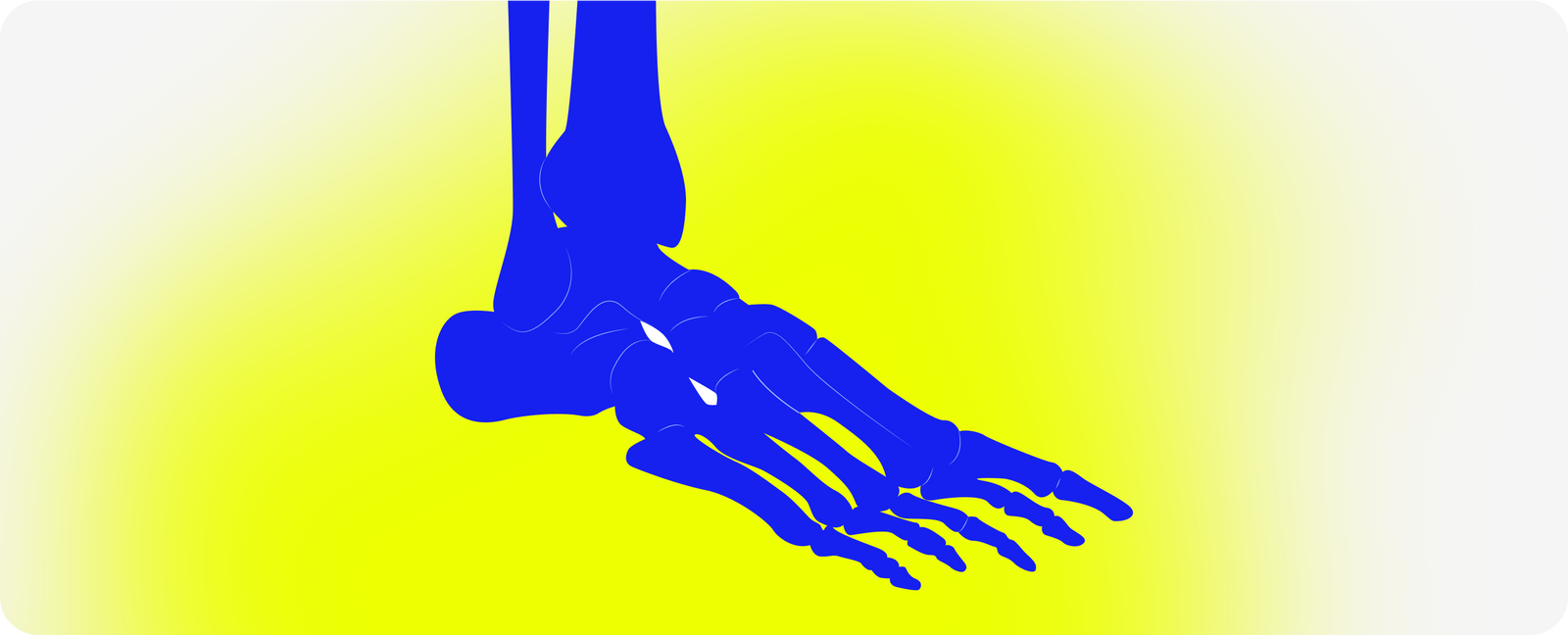

3. Hindfoot: The Heel and Ankle Complex

The hindfoot consists of the talus and calcaneus, which form the connection between the foot and the leg. The talus serves as the pivot point for the ankle joint, enabling up-and-down and side-to-side movements. The calcaneus, or heel bone, is the largest bone in the foot and absorbs the initial impact of every step, making it critical for shock absorption.

Heel pain is one of the most common complaints associated with the hindfoot and often stems from conditions such as plantar fasciitis or heel spurs. These issues can significantly affect mobility, highlighting the importance of wearing supportive footwear and seeking timely medical care (Shah & Reddy, 2020).

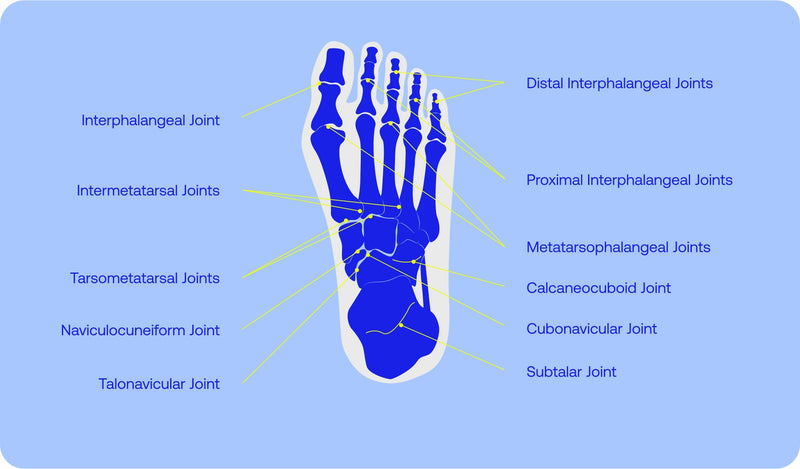

Joints: The Keys to Movement

Joints are the meeting points of bones and are pivotal in facilitating movement. The 33 joints of the foot work in unison to allow for better flexibility and stability across a variety of terrains and activities.

-

Ankle Joint: This hinge-like joint connects the foot to the leg and allows for dorsiflexion (lifting the foot upward) and plantarflexion (pointing the toes downward). It plays a fundamental role in walking, running, and jumping by enabling smooth transitions between movements.

-

Subtalar Joint: Located beneath the talus, the subtalar joint permits side-to-side motions, allowing the foot to adapt to uneven surfaces. This adaptability is crucial for maintaining balance and preventing falls.

-

Toe Joints: The metatarsophalangeal joints, located at the base of the toes, are essential for the "toe-off" phase of walking and running. This is the final step in the gait cycle, where the toes push the body forward.

Healthy joint function depends on smooth cartilage surfaces and adequate cushioning. Conditions such as arthritis or overuse injuries can lead to stiffness, inflammation, and reduced mobility, emphasizing the need for proper care and early intervention.

Muscles and Tendons: The Movers and Stablizers

While the bones and joints provide the framework of the foot, the muscles and tendons are its dynamic forces, driving movement and maintaining stability. These components are divided into two primary categories: intrinsic and extrinsic muscles.

1. Intrinsic Muscles

The intrinsic muscles are located entirely within the foot. They are responsible for fine motor movements such as curling the toes and play a significant role in maintaining the arches’ stability. Weak intrinsic muscles can result in conditions like plantar fasciitis or fallen arches, both of which can hinder mobility and cause chronic discomfort (Nguyen et al., 2019).

2. Extrinsic Muscles

The extrinsic muscles originate in the lower leg and extend into the foot via tendons. These muscles are involved in more powerful movements, such as pointing the toes, lifting the foot, and stabilizing the ankle. The gastrocnemius and soleus muscles, which form the calf, connect to the calcaneus through the Achilles tendon, enabling high-energy activities like running and jumping.

3. Tendons

Tendons are the fibrous tissues that connect muscles to bones, facilitating movement. The plantar fascia, a thick band of connective tissue running along the sole, plays a dual role by supporting the arch and absorbing shock during motion. Strain or overuse of tendons can lead to conditions such as Achilles tendonitis or plantar fasciitis, both of which require targeted interventions to prevent further damage (Shah & Reddy, 2020).

The Arches: Nature’s Shock Absorbers

The arches of the foot are among its most impressive features, acting as natural shock absorbers that protect the body from the impact of movement. These arches are supported by a network of bones, ligaments, and muscles, each contributing to their strength and flexibility.

-

Medial Longitudinal Arch: This arch runs along the inside of the foot and is the most prominent. It plays a critical role in absorbing shock and redistributing forces during walking and running.

-

Lateral Longitudinal Arch: Flatter and less pronounced, this arch provides stability and assists with weight-bearing activities.

-

Transverse Arch: Spanning the width of the foot, the transverse arch adjusts to varying terrains, ensuring adaptability and balance.

When the arches are compromised—whether by flat feet or excessively high arches—the resulting biomechanical issues can affect the entire kinetic chain, from the feet to the lower back. Supportive footwear, orthotics, and targeted exercises can help maintain the arches’ functionality and prevent complications.

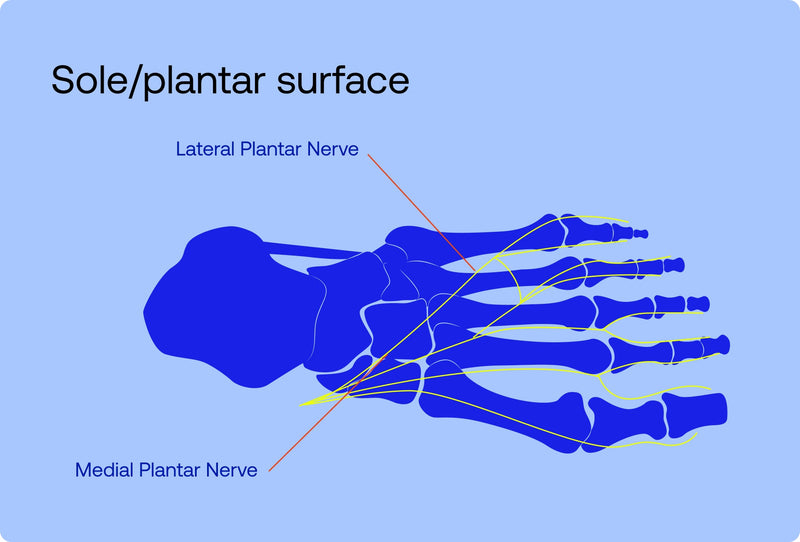

Nerves and Circulation: The Foot’s Lifeline

The foot’s nerves and blood vessels are vital for sensation, movement, and overall health. The tibial nerve and its branches provide sensory input and motor control, allowing the foot to detect subtle changes in the environment and respond accordingly.

Proper circulation, facilitated by arteries such as the dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial, ensures that oxygen and nutrients reach the foot’s tissues. Good blood flow is essential for healing wounds, maintaining skin integrity, and preventing conditions like peripheral artery disease.

Damage to nerves or blood vessels, as seen in conditions such as diabetic neuropathy, can result in numbness, reduced sensation, or delayed healing. These issues highlight the importance of regular foot checks and prompt medical attention for individuals at risk.

Common Foot Conditions

Foot problems are widespread, often stemming from overuse, improper footwear, or underlying medical conditions. Some of the most common issues include:

-

Plantar Fasciitis

This condition involves inflammation of the plantar fascia, causing sharp pain in the heel, particularly during the first steps in the morning. Risk factors include overuse, obesity, and inadequate arch support. -

Bunions

Bunions are bony deformities at the base of the big toe, often caused by genetic predisposition or wearing tight shoes. They can lead to pain, swelling, and difficulty in walking. -

Flat Feet

Flat feet occur when the arches fail to develop properly or collapse over time. This can result in uneven weight distribution, leading to discomfort and potential complications in the knees and hips. -

Heel Spurs

Heel spurs are bony growths on the underside of the heel, often associated with plantar fasciitis. They can exacerbate pain and limit mobility (Shah & Reddy, 2020).

Promoting Foot Health

Caring for the feet is essential for maintaining mobility and preventing chronic conditions. Key strategies include:

-

Proper Footwear: Shoes should provide ample support, cushioning, and room for toes to move freely.

-

Hygiene and Nail Care: Keeping feet clean and dry reduces the risk of infections, while regular nail trimming prevents ingrown toenails.

-

Strengthening Exercises: Stretching and strengthening exercises can improve flexibility, support the arches, and reduce the risk of injury.

-

Professional Care: Persistent pain or discomfort should prompt a visit to a podiatrist for accurate diagnosis and treatment.

By understanding the anatomy and mechanics of the foot, individuals can make informed choices to protect their foot health. Whether through proper footwear, targeted exercises, or regular check-ups, maintaining healthy feet is a vital step toward ensuring a lifetime of comfortable, pain-free movement.

In prioritizing foot care, one not only prevents potential problems but also gains a newfound appreciation for this extraordinary part of the human body—a true testament to the marvels of anatomy.

References

-

Hicks, J. H. (2015). The biomechanics of the human foot. In P. W. S. O'Kane (Ed.), Functional foot orthoses (pp. 25–38). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-6299-3_3

-

Nguyen, A. D., Thrasher, J. L., & Patel, A. R. (2019). Intrinsic foot muscles and their role in foot stability. Foot & Ankle Surgery, 25(1), 47-51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fas.2018.10.001

-

Shah, S. P., & Reddy, A. D. (2020). Plantar fasciitis: A comprehensive review of pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and treatment options. Journal of Foot and Ankle Research, 13(1), 45-55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13047-020-00423-4

- Zulkifly, M. M., Mohd Fadli, M., & Rosli, A. R. (2018). The impact of bunions on foot function and quality of life: A literature review. Journal of the Malaysian Orthopaedic Association, 34(2), 55-62. https://doi.org/10.5704/MOAJ.2018.0030